This week on Bad at Sports I interview Martina AltSchaefer.This is the first of two interviews with German artists I conducted on the island of Elba, Italy. Martina AltSchaefer is an artist living in Rüssellsheim, Germany. She studied with the famed Konrad Kapheck and her creative work centers on very large, labor-intensive drawing in colored pencil on translucent paper. AltSchaefer has exhibited in many prestigious galleries and museums. She also does printmaking and is an expert on mezzotint, about which she has curated shows and written essays. She was in an invitational retreat in July as a working guest of a foundation on the island of Elba along with Viennese jazz pianist and composer Martin Reiter, New York playwright Sony Sobieski, Berlin artist Alexander Johannes Kraut (the interviewee in part two) and me, Mark Staff Brandl, the EuroShark, Bad at Sports Continental and now also islandal European Bureau. And for all the Napoleon fans, especially those commenting on Facebook, they were not in exile and even Mark was allowed back on the mainland without having to invade it.

Link: http://badatsports.com/

Direct page link: http://badatsports.com/2010/episode-272-martina-altschaefer/

This is an art blog based in Europe, primarily Switzerland, but with much about the US and elsewhere. With the changes in blogging and social media, it is now a more public storage for articles connected to discussions occurring primarily on facebook and the like.

(Site in English und Deutsch)

16 November 2010

17 October 2010

Brandl Dissertation On-Line

(Click on image to view enlarged.)

The final central chapters to my PhD dissertation, Metaphor(m): Engaging a Theory of Central Trope in Art, in almost finished form, are now up on my website. That is, Chapters Four, Five, Six, Seven, Eight and Nine. Please check them out including the accompanying Covers paintings at the beginning and sequential comic art sequences at the end of each. They are titled:

Link to the dissertation on-line here.

19 September 2010

10 April 2010

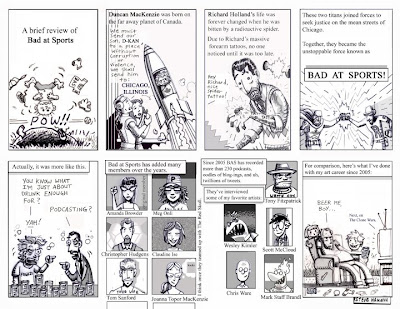

Bad at Sports exhibition at Apexart Gallery NYC --- With extra special guests!

Over the past two months everyone at Bad at Sports has been in a frenzy preparing for the exhibition, "Don't Piss On Me And Tell Me It's Raining" at apexart in New York. The show was a bit of a last-minute golden opportunity, so details have been scarce, but we now have the full scoop on what's in store, and it's pretty awesome. (You can keep up with Meg, Duncan, Amanda, Tom and Richard throughout the show's installation and opening events by following Bad at Sports on Twitter and the hashtag #basapex.) The exhibition features over 100 objects, images and ephemera that will serve as a visual complement to Bad at Sports' considerable audio archives, submitted by Bad at Sports contributors and guests of the show, including:

Carol Becker, Britton Bertran, Temporary Services, Adam Brooks and Mathew Wilson, Ivan Brunetti, Tom Burtonwood, David Coyle, Death by Design, Elizabeth Chodos, Miguel Cortez, Tony Fitzpatrick, Rob Davis and Michael Langlois, Jeremy Deller, Lisa Dorin, Jim Duignan, Dan Devening, Cody Hudson, Jason Dunda, Fendry Ekel, James Elkins, Anthony Elms, Pete Fagundo, Mary Rachel Fanning,Tony Feher, Rochelle Feinstein, Pamela Fraser, Liam Gillick, Helidon Gjergji, Michelle Grabner, Dylan Graham, Madeleine Grynsztejn, Sarah Guernsey, Terence Hannum, Anni Holm, Brian Holmes, Astrid Honold, Christopher Hudgens, Meg Onli, Amanda Browder, Tom Sanford, Duncan MacKenzie, Christian Kuras, Ben Tanner, Scott Hug, Richard Holland, Carol Jackson, Paddy Johnson, David Jones, Alex Jovanovic, Atsushi Kaga, Mark Staff Brandl, Vera Klement, Peter Saul, Gregory Knight, Monique Meloche, Leo Koenig, Chad Kouri, Steve Lacy, Caroline Picard, Jose Lerma, Laura Letinsky, Kerry James Marshall, Ed Marszewski, Eric May, Dominic Molon, Anne Elizabeth Moore, David Morgan, Julian Myers, Gavin Turk, Liz Nofziger, Jamisen Ogg, Neysa Page-Lieberman, Trevor Paglan, Raymond Pettibon, John Phillips, Allison Peters Quinn, Lane Relyea, Lawrence Rinder, David Robbins, Thomas Robertello, Julie Rodriguez Widholm, Elvia Rodriguez, Nathan Rogers-Madsen, James Rondeau, Marlene Russum Scott, Alison Ruttan, Steve Litsios, Dan S. Wang, Stephanie Smith, Deb Sokolow, Scott Speh, Chris Sperandio, Lisa Stone, Shannon Stratton, Randall Szott, Christine Tarkowski, Tony Tasset, Tracy Marie Taylor, Ron Terada, Philip von Zweck, Hamza Walker, Chris Walla, John Wanzel, Chris Ware, Oli Watt, Tony Wight, Anne Wilson, Jay Wolke, InCubate, Curtis Mann, Alex Meszmer and Reto Müller, Michael Velliquette, Clare Britt, Shannon Stratton, Damian Duffy, William Conger, M N Hutchinson, Mark Francis, Annika Marie, the artists of Blunt Art Text, and more.

The exhibition also features three related exhibition talks, all of which are free and open to the public. They'll all be rebroadcast on upcoming episodes of Bad at Sports' podcast, for those of you not able to catch the events in NYC.

You can download the exhibition brochure, which features a conversation between co-founders Duncan MacKenzie and Richard Holland about the history of Bad at Sports, here.

09 April 2010

Brandl Dissertation Chapter Three: Excursus

This is Chapter Three of my PhD dissertation (thus the fourth on-line following the Prelude and Chapters One and Two which I already posted). This chapter is in comic form and in it I begin to apply my theory to my own work as well as that of others.

The Chapters are permanently archived on my website here, but I am posting a notification on Sharkforum as I finish them and they are critiqued and approved. (I am writing under the direction of Prof. Philip Urspung at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. My second reader is Prof. Andreas Langlotz at the University of Basel, Switzerland.) This is also to offer a location where any reader who wants to can post comments, most of which will go into my final dissertation project in some fashion. I would love your comments, criticism, tangential thoughts and more!

Link to chapter here (in pdf).

Please be aware that by commenting here, you are giving me permission to use your words, with proper citation including your name, in some fashion in my final book and exhibition.

All elements are (c) and TM 2010 by Mark Staff Brandl.

Brandl Dissertation Chapter Two, The Theory of Central Trope: Metaphor and Meta-Form

This is Chapter Two of my PhD dissertation (thus the third on-line following the Prelude and Chapter One which I already posted). This is the key chapter, as it fully elucidates my theory.

The Chapters are permanently archived on my website here, but I am a post of notification up on Sharkforum as I finish them and they are critiqued and approved. (I am writing under the direction of Prof. Philip Urspung at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. My second reader is Prof. Andreas Langlotz at the University of Basel, Switzerland.). This is also to offer a location where any reader who w ants to can post comments, most of which will go into my final dissertation project in some fashion. I would love your comments, criticism, tangential thoughts and more!

Link to chapter here (in pdf).

Please be aware that by commenting here, you are giving me permission to use your words, with proper citation including your name, in some fashion in my final book and exhibition.

All elements are (c) and TM 2010 by Mark Staff Brandl.

19 March 2010

HOLLAND COTTER: Art in Review ‘#class’

Winkleman Gallery

621 West 27th Street

Chelsea

Can we talk? That seems to be an urgent art world question, partly because of an economic shakedown that sensible people — i.e., the writers of art fair news releases — keep saying is over, or never happened. But New York artists, in need of jobs or apartments or ways to pay their art school loans, are pretty sure that it did happen, and that it isn’t all that over, even if the Armory Show really had an extraspecial year.

Winkleman Gallery is doing its part to keep the conversation on the boil with an exhibition called “#class,” organized by the artists Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida, who is on loan from Schroeder Romero & Shredder Gallery. The pair have turned the main exhibition space into a combination lecture hall and conference center, with big tables, sit-up-straight chairs and wall-to-wall chalkboards in a constant process of being filled and erased as the show’s events come and go.

So far, the schedule has included discussion panels titled “Success,” “Access,” “The Ivory Tower,” “The System Works” and “Bad Curating.” To get competitive juices flowing, the artist Amanda Browder of “Bad at Sports,” a Chicago-based art podcast, offered a presentation called “Battleship,” which pitted Formalists against Conceptualists, artists against dealers, and painters against the world. A bruiser, I hear.

The art historian and critic Mira Schor, author of an excellent new book called “A Decade of Negative Thinking” (Duke University Press), read an essay on the potentially positive aspects of failure and anonymity. And the artist Joan McNeil led a panel on the notion that the art world isn’t as racially integrated as it likes to think.

So the show’s program is substantial. And there’s even something for gallerygoers in search of art on the wall. The chalkboards — think 1960s Cy Twombly — make for very entertaining reading. And Ms. Dalton and Mr. Powhida have small, conference-approved text drawings in the gallery’s back room. (They’re for sale, but with stipulations way too complicated and finicky to go into here.)

Bottom line: artists are artists’ best friends, and there should be more gatherings like this one.

Final thought: class, as in social class, is the elephant in the art fair V.I.P. rooms, in the art school studios and in Chelsea galleries. Please, can we talk? Yes we can: Friday at 2 p.m. in the gallery, the estimable art critic Ben Davis will present his “9.5 Theses on Art and Class.”

The New York Times, March 19, 2010

.

621 West 27th Street

Chelsea

Can we talk? That seems to be an urgent art world question, partly because of an economic shakedown that sensible people — i.e., the writers of art fair news releases — keep saying is over, or never happened. But New York artists, in need of jobs or apartments or ways to pay their art school loans, are pretty sure that it did happen, and that it isn’t all that over, even if the Armory Show really had an extraspecial year.

Winkleman Gallery is doing its part to keep the conversation on the boil with an exhibition called “#class,” organized by the artists Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida, who is on loan from Schroeder Romero & Shredder Gallery. The pair have turned the main exhibition space into a combination lecture hall and conference center, with big tables, sit-up-straight chairs and wall-to-wall chalkboards in a constant process of being filled and erased as the show’s events come and go.

So far, the schedule has included discussion panels titled “Success,” “Access,” “The Ivory Tower,” “The System Works” and “Bad Curating.” To get competitive juices flowing, the artist Amanda Browder of “Bad at Sports,” a Chicago-based art podcast, offered a presentation called “Battleship,” which pitted Formalists against Conceptualists, artists against dealers, and painters against the world. A bruiser, I hear.

The art historian and critic Mira Schor, author of an excellent new book called “A Decade of Negative Thinking” (Duke University Press), read an essay on the potentially positive aspects of failure and anonymity. And the artist Joan McNeil led a panel on the notion that the art world isn’t as racially integrated as it likes to think.

So the show’s program is substantial. And there’s even something for gallerygoers in search of art on the wall. The chalkboards — think 1960s Cy Twombly — make for very entertaining reading. And Ms. Dalton and Mr. Powhida have small, conference-approved text drawings in the gallery’s back room. (They’re for sale, but with stipulations way too complicated and finicky to go into here.)

Bottom line: artists are artists’ best friends, and there should be more gatherings like this one.

Final thought: class, as in social class, is the elephant in the art fair V.I.P. rooms, in the art school studios and in Chelsea galleries. Please, can we talk? Yes we can: Friday at 2 p.m. in the gallery, the estimable art critic Ben Davis will present his “9.5 Theses on Art and Class.”

The New York Times, March 19, 2010

.

14 March 2010

Dawoud Bey: History Lesson in Philadelphia

The Society of Photographic Education Meets in Philadelphia

The Society for Photographic Education held its national conference this past week in Philadelphia. I had been active as an SPE member in the 1980s and early 1990s, but hadn't attended or participated in one of the conferences for probably fifteen years or more. This years conference theme and title "Facing Diversity," along with an invitation from the conference organizers to be a featured speaker, found me in Philadelphia among some 1200 photographers and photographic educators who came from all over the country to participate in panels, show their work to portfolio reviewers and to interview for various college and university teaching positions. A wealth of other programming--both on and off site--along with the presence of a number of a number of curators, writers, and critical theorists leading and participating in provocative discussions, made for a lively and engaging four days.

At the conclusion of the conference a convocation program was held that saw a number of awards given to both students and various professionals in the field, acknowledging their works and contributions within the field. The Honored Educator was my dear friend Dr. Deborah Willis, who received an outpouring of heartfelt tributes from former students, those she has mentored over the years and her son Hank Willis Thomas that left not a dry eye in the room. My remarks that evening were dedicated to her. I wanted to provide some historical context for the gathering, since the population of attendees at these events is becoming simultaneously both older and younger. The older folks may or may not know the history leading up that moment and the younger ones just coming into the field almost certainly don't. I was pleased to be introduced by Myra Greene, my colleague in the photography department at Columbia College Chicago. The text of my remarks follow below:

"When I was asked to speak at this event I thought long and hard about what I wanted to say here and indeed if I wanted to say anything at all. Actually I thought about what needed to be said on this occasion in this place as this community gathers here in Philadelphia where over four days a wealth of ideas, thoughts and work would be presented. As a black person I have to say that I was quite honestly somewhat put off by yet another event purporting to be about “Diversity” since on the surface it appeared to be yet another ready opportunity to preach to the choir or to come to Philly and “stick it to the man” while “the man” is actually elsewhere, going about his usual dastardly business, completely ambivalent to the absence of those routinely excluded from the institutional conversation. I also am aware that the conversation about “diversity” as a specific term has gone on now for well over two decades even as during that time some things have changed while sadly more than a few things remain the same. I thought then that it would be helpful to re-examine some recent history, since I believe that it is important to be familiar with that history in order to avoid some recurring pitfalls. I am also aware that some might not know this history at all and subsequently take a lot of hard work and struggle for granted. Whatever advances have been made require an historical framework.

My interest in making photographs was crystallized in 1969 when I went to see the exhibition “Harlem On My Mind” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art when I was sixteen years old. I had never been to a museum before on my own and I have to say that actually didn’t go to the museum that day to see the exhibition. Some of you may know the contentious history of that exhibition. You might know that Benny Andrews and a multiracial group of other artists organized themselves into a group that became the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition to protest the exclusion of the voice of the black community in this this exhibition that purported to speak on their behalf. You may know that Meir Kahane formed the Jewish Defense League at that moment to protest what he felt were the anti-Semitic statements made by a young black woman student, who took the Jewish shop keepers in Harlem to task for what she considered to be their exploitative relationship with the black community. Unknown to the writer her essay had been altered and footnotes removed, making some of the quotes appear to be her own rather than words of others that she was quoting in her essay. You may or may not know that Roy DeCarava, refusing to give up control of his work in order to be in the exhibition was on the picket line, with a sign that said, “The White Folks Show the Real Nitty Gritty.” So when I set off that day from Queens, NY to go to the met I was actually going to see what all of the controversy was about, since I had read about in the local papers. As fate would have it by the time I found my way there the picket lines had vanished. Or maybe they had never come that day. At any rate I then had little choice but to go in to see the show.

Usually when I talk about the “Harlem On My Mind” exhibition I talk about seeing the photographs by James Van DerZee for the first time and how that experience informed my decision—along with my own family’s history there—to begin my first project “Harlem, USA.” But what I am in interested in looking at and revisiting this evening is the sense I got very early on of the museum as a highly contested site as the Met sought to move what it considered to be “the black experience” into the halls of a mainstream museum.

The “Harlem On My Mind” protests were not the only flashpoints taking place between artists, the larger social community and mainstream institutions. That same year Andrews and others petitioned the Whitney Museum of American Art, demanding that they be more responsive to the works of black artists. In the ensuing back and forth the BECC announced what it called “a massive boycott” of the Whitney over its decision to indeed mount an exhibition of works by black artists but with no input from them or black curatorial input. Similar protests took place at the Museum of Modern Art that same year, led by the Art Workers Coalition, a group of artists, filmmakers, writers, critics and museum staff, pressuring MoMA into implementing various reforms. These included a more open and less exclusive exhibition policy concerning the artists they exhibited and promoted: the absence of women artists and artists of color was a principal issue of contention. The coalition successfully pressured the MoMA and other museums into implementing a free admission day that still exists in certain museums to this day. All of these actions were undertaken by artists to press the issue of how to dynamically engage the museum as a pubic institution and make it more truly responsive to that public and the larger art community.

Not only were artists and their supporters protesting the lack of equitable representation on the part of mainstream public institutions, but more importantly they were forming their own organizations in order to provide the support that others were not. It is worth revisiting this history as a way of also looking forward. So let me talk a little bit about some of that history:

In 1967 the Studio Museum in Harlem was founded. The institution took its name and identity from a proposal that was written by the painter William T. Williams, whose idea it was to have a community museum for African Americans that also included studio space where members of the community could interact with black artists, and the artists would have the opportunity to more directly engage the community. Williams and fellow artist/sculptor Mel Edwards rolled up their sleeves, and with push brooms and much sweat cleared the light industrial loft space--then located over a Kentucky Fried Chicken-- in preparation for repurposing it into studios and exhibition space. The Junior Council of the Metropolitan Museum lent its backing to the fledging effort shortly thereafter. By 1969 [the very year of the Harlem On My Mind controversy] the museum mounted an exhibition, "X to the Fourth Power" that featured to work of Williams, Mel Edwards, Sam Gilliam, and Steven Kelsey (a white artist). The museum has been continually exhibiting works by black artists ever since that time. It’s first artist-in-residence was the painter LeRoy Clarke, who was joined shortly thereafter by Valerie Maynard and Lloyd Stevens. The museum has been providing work space, stipends and exhibitions to artist continuously ever since and many of those artists have gone on to become some of the most celebrated artists working in this country. The numerous publications that Studio Museum in Harlem has produced and the curators and art administrators it has trained are all testimony to its endearing importance. But it is important to remember that it began with one artist’s proposal and then another one joining him to help make that vision a physical reality, one that continues to provide much needed and extraordinary support some forty years later.

Also in 1969 the photographer, curator, writer and educator Nathan Lyons along with his wife, the artist Joan Lyons, founded the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, NY. For forty years now VSW has been provided a resource to the community of photographers and those committed to the artist book. Their publication AfterImage has been published consistently and has been an absolutely valuable source of information as well as providing an outlet for those writing on photography and media. Again, it was two artists who undertook the hard work needed to create, build and sustain this institution.

Another history lesson: In 1974 five New York Puerto Rican photographers—Charles Biasiny-Rivera, Roger Caban, George Malave, Phil Dante and Nestor Cortijo--came together to found an organization that became En Foco. While initially formed to create exhibition opportunities locally for their work and others, the organization for over thirty-five years now has exhibited, published and otherwise promoted the works of hundreds of photographers of color and provided workshops, portfolio viewings and other programming that have probably—both directly and by extension—benefited thousands of photographers as well as providing a resource for other institutions seeking the work of those photographers and artists. I know that many of you in this room today—including myself--have been the beneficiaries of the work that those five visionary photographers did as the organization has moved forward and grown over the years. It is important to remember that En Foco was not formed by someone deciding to open their doors and “diversify” or otherwise reconsider their pattern of exclusion. It was founded by photographers, by five Newyoricans who had a vision and attached a plan to it and did the hard work needed to make it a reality. So let’s acknowledge Miriam Romais and the current staff of EnFoco for the work they continue to do.

Let me continue with this history lesson: Around that same time in 1973 two former Syracuse University students Phil Block and Tom Bryan set up and began running the Community Darkrooms, a public access photography facility they had created by petitioning the University for much needed work space for area photographers. Community Darkrooms soon expanded and became Light Work/Community Darkrooms. Phil and Tom then brought in Jeffrey Hoone, who became and remained the director of Light Work from 1982 until recently, bringing in Hannah Frieser to continue the work of this extraordinary organization. Light Work’s residency program has provided an opportunity for hundreds of photographers over the years to have the necessary support to pursue their work in an absolutely supportive environment, and to disseminate that work through the publication Contact Sheet, which they grew from an 11X17 folded black ink broadside into a major publication which regularly puts that work in front of an audience of thousands. It would seem to me that we as photographers should be paying them for this, but no, they pay us while also providing this ongoing support through their residency and publication program. The existence of Light Work and its extraordinary growth makes it clear the power we each have to be the ones to make the difference that we need. I’d like to ask Jeff Hoone to stand so we can acknowledge his hard work on our behalf along with Hannah Frieser and current Light Work staff.

I could repeat these story in so many other ways by talking about so many other institutions. I could talk about Exit Art, which was founded by the artist Papo Colo and Jeanette Ingberrman, or Autograph, which was founded by several black photographers in London in 1988 who had previously started a group called D-Max, or we can talk about GASP Arts, founded five years ago by artist Magdalena Campos Pons and her husband, the musician Neil Leonard. I had a wonderful pleasure last night of participating in an event at the Philadelphia Photo Art Center, a new organization here in Philadelphia that is being run by two young photographers, Stephanie Solfa and Christopher Gianunzio, who are doing some really meaningful work right here in this community, creating opportunities and infrastructure for photographers here in Philly. All of these people, and others too numerous to mention, and some I don’t even know remind us what it is we as a community need to continue to do if we are to ensure our survival. There is no one else, quite frankly, but us. As the saying goes, “We are indeed the ones we have been waiting for.” I think we always have been and we always will be.

I believe that it is this self initiative, along with continuous public and vocal agitation insisting that public institutions be truly reflective of the public that sustains them by their tax dollars as well as demanding that public institutions reflect the very nature of the society in which they are situated, that will bring about the change that we both want and need. It was those public demonstrations, protests, writings and other forms of agitation that created whatever inroads were made over the past several decades. And progress has been made, but only because it was demanded. If you want an example of what happens when we fail to publicly agitate for change, what happens when we let our guard down, what happens when we stop letting people know that we have the capacity to get seriously pissed off if we are disrespected, one has only to look as far as the current Whitney Biennial. In an exhibition that ironically uses an image of Barack Obama on the catalogue cover, we find among other things absolutely no Latino artists and a total of three black artists among fifty-five artists in the exhibition. Artists from other non-white cultures are also underrepresented or not represented at all. What is your response to that? What would the response have been in 1969? I can’t imagine that this kind of situation would have been tolerated at that moment. Perhaps because there have been some changes over these past decades that we have become complacent or less vigilant. After all a few people of color have received MacArthur Fellowships, Rome Prizes, Guggenheim Fellowships and other forms of significant recognition. Some of us may have books, commercial gallery exhibitions, residencies where others pay us to simply do the work we want to do. I’m one of them And others here tonight are also among those fortunate enough to have have made important inroads, all due to those who came and agitated before us. So it’s easy to think the work is done, the struggle over. And yes, it’s frustrating to realize that even as progress is being made pressure must still be continuously applied.

And then along comes the Whitney Biennial 2010 to remind us just how little some things have changed as far as some people are concerned and why we must continue to agitate for an inclusive presence. With all of the profound problems we are facing as a country right now and for all of the frustration that grows out of a seeming inability to directly affect real and sustained social and political change, some have said that the progressive movement in this country is experiencing a kind of collective depression and that this explains the eerie silence surrounding so much of political discourse from the left at this moment. I wonder if those of us who have struggled so long in our various arenas may not also be suffering from a kind of battle fatigue? One thing I do know is that those who would like to maintain the status quo of exclusion never seem to get tired of doing so. And we must never tire of letting them know that we belong at the table as much as anyone else, even as go about the business of building our own tables.

So what to do? I don’t think it’s for me to come here tonight and answer that question. Rather I can only hope that through the example of history we get a sense of what needs to be done. Finally, I’d like to share a few thoughts on “Diversity,” since that is the theme of this conference. Diversity to me implies that there is still some normative paradigm at the center that we are seeking to destabilize rather than doing away with it in favor of something quite different. It suggests that institutions have an inherently white and male identity that needs to be added to. To operate out of this paradigm is, of course, a kind of tokenism by yet another name and seeks to trade on the momentary (but always empty and short lived) self-congratulatory excitement of seeing a new color in still unexpected places. It would seem to me that by now we should be approaching a point where anyone should be expected to be anywhere. I think it's time to turn away from "diversity" as an operative objective and turn instead towards the more meaningful and substantial goal of making institutional spaces ever more inclusive and embrace the goal of inclusivity, in which everyone's identity is central to the whole. One way to accomplish this is to consider how in fact the institution's identity can be meaningfully transformed and expanded conceptually by this enhanced inclusiveness in a way to deeply transforms the very nature of that institution. Inclusivity implies a desire to actually change through institutional expansion, while diversity implies to me that those being brought in have to simply fit into the normative and dominant existing paradigms and simply add "color" to it.

In the end of the day we still need to agitate for a transformed worldview within institutional culture that embraces the truly global and multiracial character of our human community.

Anything less than that should met with continuing, vocal and vociferous protest."

See more Bey posts at his blog, What's Going On?

Clifford Meth's Welcome to Hollywood and His Sharky Response

As Rich Johnston writes, "Earlier this week, writer Clifford Meth revisited his rather-abandoned-of-late column at Comic Bulletin, Meth Addict.In which he told how a project he was associated with, Dave Cockrum's The Futurians almost made it to the screen a couple of times.And how he was also hired to write a screenplay treatment for his IDW series Snaked, before being moved aside for another writer - and then discovering he was suddenly not getting paid his kill fee...

"We have a contract," I said. "Of course he's going to pay me." "No he isn't. He's pretty sure you won't sue him. The fee is too small and you'd have to fly to Los Angeles to file for damages. Apparently this is how he does things." "Tell me this is a bad joke." "Sorry Cliff," said my agent. "Welcome to Hollywood."

So Cliff describes how he offered to "talk" with the producer's parents. Whose address Meth happened to have. Which suddenly has the desired effect.The column has been pulled, after someone got a bit scared it seems. But I understand the specific column in question has been bought out by a bigger site who will be running it tomorrow.

Not Bleeding Cool, we weren't even in the bidding. But if you'd like to read the whole column now, go to Daniel Best's Blog, where it is re-posted here.

07 March 2010

Noah Berlatsky: "Artists Write: The Last Shall Be First"

Proximity continues its Arts Theory Column, edited by Mark Staff Brandl, with an essay by Noah Berlatsky: "The Last Shall Be First."

Most traditional economic theory is built around the concept of scarcity -- the idea that there's not enough stuff to go around. In The Accursed Share (1946), famed theorist Georges Bataille inverts this; life, he says, is characterized, not by too little, but by too much. Life is excess -- it pushes onto every bleak rock, every cranny; it spends itself in profligate sexual activity and in the ultimate profligacy of death. And it throws out unneeded economic activity; too much fat, too many children, too much grain in the stores, too many bodies in the street, too much creative energy shaking its collective tuchas on the YouTube videos.

Reblog this post [with Zemanta]

For Bataille, it is the business of life and of society to consume this "accursed share". The paradigmatic way to do this is through sacrifice; the burning of goods -- or, better, of lives -- with no recompense. Through sacrifice, Bataille argues, the blasphemous impulse to turn other creatures, other lives, into productive things, is reversed, acknowledged as false and evil. To respect the universe, abundance must be spent, not horded. The Aztecs, in burning men, honored life.

The bloody Aztec rituals were paradigmatic; the North American Indian custom of potlatch, on the other hand, was, for Bataille, a sinister travesty. In the potlatch, an Indian would give a valuable gift to a rival to demonstrate his own wealth and power. In response, a rival would have to give an even greater gift. This could go on and on, back and forth, and whoever ended by giving the greatest gift would show himself superior. Thus, squander was not in fact squander -- the winner did not lose his gift, but instead traded it for prestige, or rank. Bataille thus notes contemptuously that potlatch "attempts to grasp that which it wished to be ungraspable, to use that whose utility it denied." By turning sacrifice into rank, Bataille believed, potlatch turns, not a part, but the whole of the universe to a servile thing.

...in the modern day, the avatar of Bataille's twisted potlatch is none other than the artist, in all his or her needy, self-deluding, miserly profligacy

Potlatch as such is now practiced in only a handful of places, and (to be remorselessly PC) one has to wonder whether Bataille's anthropological account really did the custom justice. Still, if Native Americans don't exactly recognize Bataille's potlatch, others, I think would. Who, after all, profligately spends time, energy, and resources in a remorseless quest for status and rank? Who grasps the sacred and turns it to the profane ends of thingness? Who wastes, not in the name of a sublime nothing, but in the pursuit of a soiled, excess something?

The answer is clear enough: in the modern day, the avatar of Bataille's twisted potlatch is none other than the artist, in all his or her needy, self-deluding, miserly profligacy. The artist hunkers down with her or his materials, practicing, practicing, practicing, wasting life in the pursuit of an entirely useless form--and for what? Why to be noticed, admired, proclaimed a genius--in short, for rank. True, some artists, the least debased, seek, not some subcultural caché, but simply money. They are guilty only of the typical human failing; the desire to turn bits of life into things; to treat the sacred as a business proposition. Beyoncé and Rod Stewart are no more despicable than, say, Bill Gates, or your average carpenter. But by far the vast majority of artists forswear (relatively) healthy capitalism for the putrid wallowing in essences; they desire to turn life itself "authenticity" into a bludgeon with which to beat their rivals. The Aztecs tore out hearts to offer to the Sun God; artists pour out heart and soul and offer it to Pitchfork reviewers.

That is not to say that all artists are inevitably defiled. On the contrary, if any contemporary figure attains to Bataille's ideal of pure sacrifice it is one particular kind of artist--that is, the failed artist. Note that by "failed" here, I do not mean the artist who has missed commercial success, but has underground cred or aesthetic bonafides, or who is discovered and lionized after his death. On the contrary. When I say "failed" I mean "failed." I mean an artist who profligately, copiously, obsessively works on creating objects that are, literally--by everyone and forever--unwanted. Creators of tuneless songs that never achieve dissonance; of ugly canvases too self-conscious to be outsider art; of doggerel verse too banal for even the high school literary magazine--in them, the excess of the universe is annihilated. Genius, love, life--are exchanged for neither lucre, nor cred, nor beauty, but are instead simply thrown away. Failed art is permanently wasted, and it is therefore sacred. Squatting amidst the gross outpouring of sublimity, the ugly, the thumb-fingered, the clichéd piece of crap, is alone sacred.

Proximity magazine here.

27 February 2010

Lamis El Farra, Painting Show in the Collapsible Kunsthalle

The Collapsible Kunsthalle: documentation of the latest exhibition, "Faces," paintings by Lamis El Farra. Trogen, Switzerland, Galerei am Landesgemeindeplatz.

Link here.

16 February 2010

Short Video Interview with Brandl at CAA on Columbia College Blog

Barabra Trinh says, "While I’m sitting waiting for a session to begin, my curiosity was sparked when a man in front of me was enthusiastically speaking about comics and his art on the T-shirt he was currently wearing. Instead of handing someone an ordinary business card, he hands them a button with his contact info on the back. That is because Mark Staff Brandl (http://www.markstaffbrandl.com/) is no ordinary artist. He is interested in comic/ sequential art, painting, and art history. His installations are described as ‘walk in comic books’, a mixture of installation and comic books that are 12 ft tall. In the video, Mark tells us about himself and his experience at CAA."

Barbara Trinh, BA Candidate from the Film & Video Dept

01 February 2010

Student Comics KSL 2010

Comics by the Students in the 2-day Class in the Kunstschule Liechtenstein

(Art Academy of Liechtenstein)

in March 2010 with Mark Staff Brandl.

(click on comics to view enlarged)

(click on comics to view enlarged)

25 January 2010

Brandl: Post-Hysterical: Timeline, Comics and a Plurogenic View of Art History

A 55 minute speech, with images, by artist and art historian Mark Staff Brandl. Originally presented at the CAA (College Art Association, art historians organization) annual conference, as well as at the Kunstschule Lichtenstein, in 2010. It concerns description and criticism of the standard conceptions and models of fine art history and the history of comics, while offering a new one model for conceiving of and teaching these histories.

09 January 2010

Stephen Hicks: Why Art Became Ugly

Why Art Became Ugly

by Stephen Hicks

For a long time critics of modern and postmodern art have relied on the "Isn't that disgusting" strategy. By that I mean the strategy of pointing out that given works of art are ugly, trivial, or in bad taste, that "a five-year-old could have made them," and so on. And they have mostly left it at that. The points have often been true, but they have also been tiresome and unconvincing—and the art world has been entirely unmoved. Of course, the major works of the twentieth-century art world are ugly. Of course, many are offensive. Of course, a five-year old could in many cases have made an indistinguishable product. Those points are not arguable—and they are entirely beside the main question. The important question is: Why has the art world of the twentieth-century adopted the ugly and the offensive? Why has it poured its creative energies and cleverness into the trivial and the self-proclaimedly meaningless?

It is easy to point out the psychologically disturbed or cynical players who learn to manipulate the system to get their fifteen minutes or a nice big check from a foundation, or the hangers-on who play the game in order to get invited to the right parties. But every human field of endeavor has its hangers-on, its disturbed and cynical members, and they are never the ones who drive the scene. The question is: Why did cynicism and ugliness come to be the game you had to play to make it in the world of art?

My first theme will be that the modern and postmodern art world was and is nested within a broader cultural framework generated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite occasional invocations of "Art for art's sake" and attempts to withdraw from life, art has always been significant, probing the same issues about the human condition that all forms of cultural life probe. Artists are thinking and feeling human beings, and they think and feel intensely about the same important things that all intelligent and passionate humans do. Even when some artists claim that their work has no significance or reference or meaning, those claims are always significant, referential, and meaningful claims. What counts as a significant cultural claim, however, depends on what is going on in the broader intellectual and cultural framework. The world of art is not hermetically sealed—its themes can have an internal developmental logic, but those themes are almost never generated from within the world of art.

My second theme will be that postmodern art does not represent much of a break with modernism. Despite the variations that postmodernism represents, the postmodern art world has never challenged fundamentally the framework that modernism adopted at the end of the nineteenth century. There is more fundamental continuity between them than discontinuity. Postmodernism has simply become an increasingly narrow set of variations upon a narrow modernist set of themes. To see this, let us rehearse the main lines of development.

Modernism's Themes

By now the main themes of modern art are clear to us. Standard histories of art tell us that modern art died around 1970, its themes and strategies exhausted, and that we now have more than a quarter-century of postmodernism behind us.

The big break with the past occurred toward the end of the nineteenth century. Until the end of the nineteenth century, art was a vehicle of sensuousness, meaning, and passion. Its goals were beauty and originality. The artist was a skilled master of his craft. Such masters were able to create original representations with human significance and universal appeal. Combining skill and vision, artists were exalted beings capable of creating objects that in turn had an awesome power to exalt the senses, the intellects, and the passions of those who experience them.

The break with that tradition came when the first modernists of the late 1800s set themselves systematically to the project of isolating all the elements of art and eliminating them or flying in the face of them.

The causes of the break were many. The increasing naturalism of the nineteenth century led, for those who had not shaken off their religious heritage, to feeling desperately alone and without guidance in a vast, empty universe. The rise of philosophical theories of skepticism and irrationalism led many to distrust their cognitive faculties of perception and reason. The development of scientific theories of evolution and entropy brought with them pessimistic accounts of human nature and the destiny of the world. The spread of liberalism and free markets caused their opponents on the political Left, many of whom were members of the artistic avant garde, to see political developments as a series of deep disappointments. And the technological revolutions spurred by the combination of science and capitalism led many to project a future in which mankind would be dehumanized or destroyed by the very machines that were supposed to improve its lot.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the nineteenth-century intellectual world's sense of disquiet had become a full-blown anxiety. The artists responded, exploring in their works the implications of a world in which reason, dignity, optimism, and beauty seemed to have disappeared.

The new theme was: Art must be a quest for truth, however brutal, and not a quest for beauty. So the question became: What is the truth of art?

The first major claim of modernism is a content claim: a demand for a recognition of the truth that the world is not beautiful. The world is fractured, decaying, horrifying, depressing, empty, and ultimately unintelligible.

That claim by itself is not uniquely modernist, though the number of artists who signed onto that claim is uniquely modernist. Some past artists had believed the world to be ugly and horrible—but they had used the traditional realistic forms of perspective and color to say this. The innovation of the early modernists was to assert that form must match content. Art should not use the traditional realistic forms of perspective and color because those forms presuppose an orderly, integrated, and knowable reality.

Edvard Munch got there first (The Scream, 1893): If the truth is that reality is a horrifying, disintegrating swirl, then both form and content should express the feeling. Pablo Picasso got there second (Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907): If the truth is that reality is fractured and empty, then both form and content must express that. Salvador Dali's surrealist paintings go a step further: If the truth is that reality is unintelligible, then art can teach this lesson by using realistic forms against the idea that we can distinguish objective reality from irrational, subjective dreams.

The second and parallel development within modernism is Reductionism. If we are uncomfortable with the idea that art or any discipline can tell us the truth about external, objective reality, then we will retreat from any sort of content and focus solely on art's uniqueness. And if we are concerned with what is unique in art, then each artistic medium is different. For example, what distinguishes painting from literature? Literature tells stories—so painting should not pretend to be literature; instead it should focus on its own uniqueness. The truth about painting is that it is a two-dimensional surface with paint on it. So instead of telling stories, the reductionist movement in painting asserts, to find the truth of painting painters must deliberately eliminate whatever can be eliminated from painting and see what survives. Then we will know the essence of painting.

Since we are eliminating, in the following iconic pieces from the twentieth century world of art, it is often not what is on the canvas that counts - it is what is not there. What is significant is what has been eliminated and is now absent. Art comes to be about absence.

Many elimination strategies were pursued by the early reductionists. If, traditionally, painting was cognitively significant in that it told us something about external reality, then the first thing we should try to eliminate is content based on an alleged awareness of reality. Dali's Metamorphosis here does double-duty. Dali challenges the idea that what we call reality is anything more than a bizarre subjective psychological state. Picasso's Desmoiselles also does double-duty: If the eyes are the window to the soul, then these souls are frighteningly vacant. Or if we turn the focus the other way and say that our eyes are our access to the world, then Picasso's women are seeing nothing.

So we eliminate from art a cognitive connection to an external reality. What else can be eliminated? If traditionally, skill in painting is a matter of representing a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface, then to be true to painting we must eliminate the pretense of a third dimension. Sculpture is three-dimensional, but painting is not sculpture. The truth of painting is that it is not three-dimensional. For example, Barnett Newman's Dionysius (1949)— consisting of a green background with two thin, horizontal lines, one yellow and one red—is representative of this line of development. It is paint on canvas and only paint on canvas.

But traditional paints have a texture, leading to a three-dimensional effect if one looks closely. So, as Morris Louis demonstrates in Alpha-Phi (1961), we can get closer to painting's two-dimensional essence by thinning down the paints so that there is no texture. We are now as two-dimensional as possible, and that is the end of this reductionist strategy—the third dimension is gone.

On the other hand, if painting is two-dimensional, then perhaps we can still be true to painting if we paint things that themselves are two-dimensional. For example, Jasper Johns's White Flag (1955-58) is a painted-over American flag, and Roy Lichtenstein's Drowning Girl (1963), Whaam! (1963; Figure 4), and others are over-sized comic-book panels blown up onto large canvases. But flags and comic books are themselves two-dimensional objects, so a two-dimensional painting of them retains their essential truth while letting us remain true to the theme of painting's two-dimensionality. This device is particularly clever because, while remaining two-dimensional, we can at the same time smuggle in some illicit content—content that earlier had been eliminated.

But of course that really is cheating, as Lichtenstein went on to point out humorously with his Brushstroke (1965). If painting is the act of making brushstrokes on canvas, then to be true to the act of painting the product should look like what it is: a brushstroke on canvas. And with that little joke, this line of development is over.

So far in our quest for the truth of painting, we have tried only playing with the gap between three-dimensional and two-dimensional. What about composition and color differentiation? Can we eliminate those?

If, traditionally, skill in painting requires a mastery of composition, then, as Jackson Pollock's pieces famously illustrate, we can eliminate careful composition for randomness. Or if, traditionally, skill in painting is a mastery of color range and color differentiation, then we can eliminate color differentiation. Early in the twentieth century, Kasimir Malevich's White on White (1918) was a whitish square painted on a white background. Ad Reinhardt's Abstract Painting (1960-66) brought this line of development to a close by showing a very, very black cross painted on a very, very, very black background.

Or if traditionally the art object is a special and unique artifact, then we can eliminate the art object's special status by making art works that are reproductions of excruciatingly ordinary objects. Andy Warhol's paintings of soup cans and reproductions of tomato juice cartons have just that result. Or in a variation on that theme and sneaking in some cultural criticism, we can show that what art and capitalism do is take objects that are in fact special and unique—such as Marilyn Monroe—and reduce them to two-dimensional mass-produced commodities (Marilyn (Three Times), 1962).

Or if art traditionally is sensuous and perceptually embodied, then we can eliminate the sensuous and perceptual altogether, as in conceptual art. Consider Joseph Kosuth's It was It, Number 4. Kosuth first created a background of type-set text that reads:

Observation of the conditions under which misreadings occur gives rise to a doubt which I should not like to leave unmentioned, because it can, I think, become the starting-point for a fruitful investigation. Everyone knows how frequently the reader finds that in reading aloud his attention wanders from the text and turns to his own thoughts. As a result of this digression on the part of his attention he is often unable, if interrupted and questioned, to give any account of what he has read. He has read, as it were, automatically, but not correctly.

He then overlaid the black text with the following words in blue neon:

Description of the same content twice.

It was it.

Here the perceptual appeal is minimal, and art becomes a purely conceptual enterprise— and we have eliminated painting altogether.

If we put all of the above reductionist strategies together, the course of modern painting has been to eliminate the third dimension, composition, color, perceptual content, and the sense of the art object as something special.

This inevitably leads us back to Marcel Duchamp, the grand-daddy of modernism who saw the end of the road decades earlier. With his Fountain (1917; Figure 6), Duchamp made the quintessential statement about the history and future of art. Duchamp of course knew the history of art and, given recent trends, where art was going. He knew what had been achieved—how over the centuries art had been a powerful vehicle that called upon the highest development of the human creative vision and demanded exacting technical skill; and he knew that art had an awesome power to exalt the senses, the minds, and the passions of those who experience it. With his urinal, Duchamp offered presciently a summary statement. The artist is not a great creator—Duchamp went shopping at a plumbing store. The artwork is not a special object—it was mass-produced in a factory. The experience of art is not exciting and ennobling—it is puzzling and leaves one with a sense of distaste. But over and above that, Duchamp did not select just any ready-made object to display. He could have selected a sink or a door-knob. In selecting the urinal, his message was clear: Art is something you piss on.

But there is a still deeper point that Duchamp's urinal teaches us about the trajectory of modernism. In modernism, art becomes a philosophical enterprise rather than an artistic one. The driving purpose of modernism is not to do art but to find out what art is. We have eliminated X —is it still art? Now we have eliminated Y —is it still art? The point of the objects was not aesthetic experience; rather the works are symbols representing a stage in the evolution of a philosophical experiment. In most cases, the discussions about the works are much more interesting than the works themselves. That means that we keep the works in museums and archives and we look at them not for their own sake, but for the same reason scientists keep lab notes—as a record of their thinking at various stages. Or, to use a different analogy, the purpose of art objects is like that road signs along the highway—not as objects of contemplation in their own right but as markers to tell us how far we have traveled down a given road.

This was Duchamp's point when he noted, contemptuously, that most critics had missed the point: "I threw the bottle rack and the urinal into their faces as a challenge, and now they admire them for their aesthetic beauty." The urinal is not art—it is a device used as part of an intellectual exercise in figuring out why it is not art.

Modernism had no answer to Duchamp's challenge, and by the 1960s it found it had reached a dead end. To the extent modern art had content, its pessimism led it to the conclusion that nothing was worth saying. To the extent that it played the reductive elimination game, it found that nothing uniquely artistic survived elimination. Art became nothing. In the 1960s, Robert Rauschenberg was often quoted as saying, "Artists are no better than filing clerks." And Andy Warhol found his usual smirking way to announce the end when asked what he thought art was anymore: "Art? —Oh, that's a man's name."

Postmodernism's Four Themes

Where could art go after death of modernism? Postmodernism did not go, and has not gone, far. It needed some content and some new forms, but it did not want to go back to classicism, romanticism, or traditional realism.

As it had at the end of the nineteenth century, the art world reached out and drew upon the broader intellectual and cultural context of the late 1960s and 1970s. It absorbed the trendiness of Existentialism's absurd universe, the failure of Positivism's reductionism, and the collapse of socialism's New Left. It connected to intellectual heavyweights such as Thomas Kuhn, Michel Foucault, and Jacques Derrida, and it took its cue from their abstract themes of antirealism, deconstruction, and their heightened adversarial stance to Western culture. From those themes, postmodernism introduced four variations on modernism.

First, postmodernism re-introduced content—but only self-referential and ironic content. As with philosophical postmodernism, artistic postmodernism rejected any form of realism and became anti-realist. Art cannot be about reality or nature—because, according to postmodernism, "reality" and "nature" are merely social constructs. All we have are the social world and its social constructs, one of those constructs being the world of art. So, we may have content in our art as long as we talk self-referentially about the social world of art.

Secondly, postmodernism set itself to a more ruthless deconstruction of traditional categories that the modernists had not fully eliminated. Modernism had been reductionist, but some artistic targets remained.

For example, stylistic integrity had always been an element of great art, and artistic purity was one motivating force within modernism. So, one postmodern strategy has been to mix styles eclectically in order to undercut the idea of stylistic integrity. An early postmodern example in architecture, for example, is Philip Johnson's AT&T (now Sony) building in Manhattan—a modern skyscraper that could also be a giant eighteenth-century Chippendale cabinet. The architectural firm of Foster & Partners designed the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation headquarters (1979-86)—a building that could also be the bridge of a ship, complete with mock anti-aircraft guns, should the bank ever need them. Friedensreich Hundertwasser's House (1986) in Vienna is more extreme—a deliberate slapping together of glass skyscraper, stucco, and occasional bricks, along with oddly placed balconies and arbitrarily sized windows, and completed with a Russian onion dome or two.

If we put the above two strategies together, then postmodern art will come to be both self-referential and destructive. It will be an internal commentary on the social history of art, but a subversive one. Here there is a continuity from modernism. Picasso took one of Matisse's portraits of his daughter—and used it as a dartboard, encouraging his friends to do the same. Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) is a rendition of the Mona Lisa with a cartoonish beard and moustache added. Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning work with a heavy wax pencil. In the 1960s, a gang led by George Maciunas performed Philip Corner's Piano Activities (1962)—which called for a number of men with implements of destruction such as band saws and chisels to destroy a grand piano. Niki de Saint Phalle's Venus de Milo (1962, Figure 8) is a life-size plaster-on-chickenwire version of the classic beauty filled with bags of red and black paint; Saint Phalle then took a rifle and fired upon the Venus, puncturing the statue and the bags of paint to a splattered effect.

Saint Phalle's Venus links us to the third postmodern strategy. Postmodernism allows one to make content statements as long as they are about social reality and not about an alleged natural or objective reality and—here is the variation—as long as they are narrower race/class/sex statements rather than pretentious, universalist claims about something called The Human Condition. Postmodernism rejects a universal human nature and substitutes the claim that we are all constructed into competing groups by our racial, economic, ethnic, and sexual circumstances. Applied to art, this postmodern claim implies that there are no artists, only hyphenated artists: black-artists, woman-artists, homosexual-artists, poor-Hispanic-artists, and so on.

Conceptual artist Frederic's PMS piece from the 1990s is helpful here in providing a schema. The piece is textual, a black canvas with the following words in red:

WHAT CREATES P.M.S. IN WOMEN?

Power

Money

Sex

Let us start with Power and consider race. Jane Alexander's Butcher Boys (1985-86) is an appropriately powerful piece about white power. Alexander places three South African white figures on a bench. Their skin is ghostly or corpse-like white, and she gives them monster heads and heart-surgery scars suggesting their heartlessness. But all three of them are sitting casually on the bench—they could be waiting for a bus or watching the passers-by at a mall. Her theme is the banality of evil: Whites don't even recognize themselves for the monsters they are.

Now for Money. There is the long-standing rule in modern art that one should never say anything kind about capitalism. From Andy Warhol's criticisms of mass-produced capitalist culture we can move easily to Jenny Holzer's Private Property Created Crime (1982). In the center of world capitalism—New York's Times Square—Holzer combined conceptualism with social commentary in an ironically clever manner by using capitalism's own media to subvert it. German artist Hans Haacke's Freedom is now simply going to be sponsored—out of petty cash (1991) is another monumental example. While the rest of the world was celebrating the end of brutality behind the Iron Curtain, Haacke erected a huge Mercedes-Benz logo atop a former East German guard tower. Men with guns previously occupied that tower—but Haacke suggests that all we are doing is replacing the rule of the Soviets with the equally heartless rule of the corporations.

Now for Sex. Saint Phalle's Venus can do double-duty here. We can interpret the rifle that shoots into the Venus as a phallic tool of dominance, in which case Saint-Phalle's piece can be seen as a feminist protest of male destruction of femininity. Mainstream feminist art includes Barbara Kruger's posters and room-size exhibits in bold black and red with angry faces yelling politically correct slogans about female victimization—art as a poster at a political rally. Jenny Saville's Branded (1992, Figure 10) is a grotesque self-portrait: Against any conception of female beauty, Saville asserts that she will be distended and hideous—and shove it in your face.

The fourth and final postmodern variation on modernism is a more ruthless nihilism. The above, while focused on the negative, are still dealing with important themes of power, wealth, and justice toward women. How can we eliminate more thoroughly any positivity in art? As relentlessly negative as modern art has been, what has not been done?

Entrails and blood: An art exhibition in 2000 asked patrons to place a goldfish in a blender and then turn the blender on—art as life reduced to indiscriminate liquid entrails. Marc Quinn's Self (1991) is the artist's own blood collected over the course of several months and molded into a frozen cast of his head. That is reductionism with a vengeance.

Unusual sex: Alternate sexualities and fetishes have been pretty much worked over during the twentieth century. But until recently art has not explored sex involving children. Eric Fischl's Sleepwalker (1979) shows a pubescent boy masturbating while standing naked in a kiddie pool in the backyard. Fischl's Bad Boy (1981) shows a boy stealing from his mother's purse and looking at his naked mother who is sleeping with her legs sprawled. If we have read our Freud, however, perhaps this is not very shocking. So we move on to Paul McCarthy's Cultural Gothic (1992-93) and the theme of bestiality. In this life-size, moving exhibit, a young boy stands behind a goat that he is violating. Here we have more than child sexuality and sex with animals, however: McCarthy adds some cultural commentary by having the boy's father present and resting his hands paternally on the boy's shoulders while the boy thrusts away.

A preoccupation with urine and feces: Again, postmodernism continues a longstanding modernist tradition. After Duchamp's urinal, Kunst ist Scheisse ("Art is shit") became, fittingly, the motto of the Dada movement. In the 1960s Piero Manzoni canned, labeled, exhibited and sold ninety tins of his own excrement (in 2002, a British museum purchased can number 68 for about $40,000). Andres Serrano generated controversy in the 1980s with his Piss Christ, a crucifix submerged in a jar of the artist's urine. In the 1990s Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) portrayed the Madonna as surrounded by disembodied genitalia and chunks of dried feces. In 2000 Yuan Cai and Jian Jun Xi paid homage to their master, Marcel Duchamp. Fountain is now at the Tate Museum in London, and during regular museum hours Yuan and Jian unzipped and proceeded to urinate on Duchamp's urinal. (The museum's directors were not pleased, but Duchamp would be proud of his spiritual children.) And there is G. G. Allin, the self-proclaimed performance artist who achieved his fifteen minutes by defecating on stage and flinging his feces into the audience.

So again we have reached a dead end: From Duchamp's Piss on art at the beginning of the century to Allin's Shit on you at the end—that is not a significant development over the course of a century.

The Future of Art

The heyday of postmodernism in art was the 1980s and 90s. Modernism had become stale by the 1970s, and I suggest that postmodernism has reached a similar dead-end, a What next? stage. Postmodern art was a game that played out within a narrow range of assumptions, and we are weary of the same old, same old, with only minor variations. The gross-outs have become mechanical and repetitive, and they no longer gross us out.

So, what next?

It is helpful to remember that modernism in art came out of a very specific intellectual culture of the late nineteenth century, and that it has remained loyally stuck in those themes. But those are not the only themes open to artists, and much has happened since the end of the nineteenth century.

We would not know from the world of modern art that average life expectancy has doubled since Edvard Munch screamed. We would not know that diseases that routinely killed hundreds of thousands of newborns each year have been eliminated. Nor would we know anything about the rising standards of living, the spread of democratic liberalism, and emerging markets.

We are brutally aware of the horrible disasters of National Socialism and international Communism, and art has a role in keeping us aware of them. But we would never know from the world of art the equally important fact that those battles were won and brutality was defeated.

And entering even more exotic territory, if we knew only the contemporary art world we would never get a glimmer of the excitement in evolutionary psychology, Big Bang cosmology, genetic engineering, the beauty of fractal mathematics—and the awesome fact that humans are the kind of being that can do all those exciting things.

Artists and the art world should be at the edge. The art world is now marginalized, in-bred, and conservative. It is being left behind, and for any self-respecting artist there should be nothing more demeaning than being left behind.

There are few more important cultural purposes than genuinely advancing art. We all intensely and personally know what art means to us. We surround ourselves with it. Art books and videos. Films at the theatre and on DVD. Stereos at home, music on our Walkmans, and CD players in our cars. Novels at the beach and as bedtime reading. Trips to galleries and museums. Art on the walls of our living space. We are each creating the artistic world we want to be in. From the art in our individual lives to the art that is cultural and national symbols, from the $10 poster to the $10 million painting acquired by a museum—we all have a major investment in art.

The world is ready for the bold new artistic move. That can come only from those not content with spotting the latest trivial variation on current themes. It can come only from those whose idea of boldness is not—waiting to see what can be done with waste products that has never been done before.

The point is not that there are no negatives out there in the world for art to confront, or that art cannot be a means of criticism. There are negatives and art should never shrink from them. My argument is with the uniform negativity and destructiveness of the art world. When has art in the twentieth century said anything encouraging about human relations, about mankind's potential for dignity, and courage, about the sheer positive passion of being in the world?

Artistic revolutions are made by a few key individuals. At the heart of every revolution is an artist who achieves originality. A novel theme, a fresh subject, or the inventive use of composition, figure, or color marks the beginning of a new era. Artists truly are gods: they create a world in their work, and they contribute to the creation of our cultural world.

Yet for revolutionary artists to reach the rest of the world, others play a crucial role. Collectors, gallery owners, curators, and critics make decisions about which artists are genuinely creating—and, accordingly, about which artists are most deserving of their money, gallery space, and recommendations. Those individuals also make the revolutions. In the broader art world, a revolution depends on those who are capable of recognizing the original artist's achievement and who have the entrepreneurial courage to promote that work.

The point is not to return to the 1800s or to turn art into the making of pretty postcards. The point is about being a human being who looks at the world afresh. In each generation there are only a few who do that at the highest level. That is always the challenge of art and its highest calling.

The world of postmodern art is a run-down hall of mirrors reflecting tiredly some innovations introduced a century ago. It is time to move on.

Stephen Hicks is a professor of philosophy at Rockford College in Illinois. He is the author of Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault (Scholargy Publishing, 2004). He can be contacted through his Web site. This article is based on lectures given at the Foundation for the Advancement of Art's "Innovation, Substance, Vision" conference in New York (October 2003) and the Rockford College Philosophy Club's "The Future of Art" panel (April 2004).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)